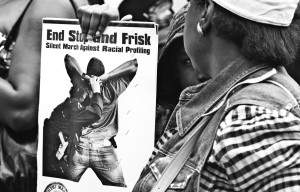

Last fall I focused the introductory composition class I taught at CUNY’s Lehman College on stop-and-frisk and racial profiling at large. The course received the 2014 Diana Colbert Innovative Teaching Prize, awarded annually by the CUNY Graduate Center’s Ph.D. Program in English. I post the materials I submitted here in the interest of open access: all of the following, except for my specific words, is free to use. If you’ve taught a similar class, let me know—perhaps we can build a site for such pedagogic and teaching materials. (Above image: “End Stop and Frisk” by sainthuck, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.)

Rationale

Black and Latino young men are highly disproportionately stopped-and-frisked by New York City police officers, particularly in the Bronx and Brooklyn. (For representative New York Police Department data collected by the New York Civil Liberties Union, see here and here.) Although the stop-and-frisk program has been in place since at least 2002, debate over its propriety and effectiveness reached a peak last summer due to the city’s mayoral election, the media attention to now-mayor Bill De Blasio’s “mixed-race” family, and a federal court’s finding that stop-and-frisk violated both the 4th and 14th Amendments. At the same time, the George Zimmerman trial, which concluded with Trayvon Martin’s killer being found not guilty, amplified controversy about racial profiling and state power. So, too, did widely noted cultural representations such as Kanye West’s Yeezus album, with songs such as “New Slaves” and “Blood on the Leaves,” a re-working of the anti-lynching anthem “Strange Fruit,” and Ryan Coogler’s film Fruitvale Station, about 22-year-old Oscar Grant, slain by Oakland transit police in 2008.

Given these various cultural texts and discourses concerning racial violence, spanning—at a minimum—the white-supremacist terrorism of the “old South” and the everyday subjugation of black and Latino New Yorkers, it seemed an especially rich conjuncture to focus my English composition class at Lehman College on stop-and-frisk and the longer history of racial profiling in the United States. Indeed, given Lehman’s Bronx location, the higher rate of stop-and-frisk in the borough (not to mention lingering grief over local teenager Ramarley Graham, killed by a cop in 2012), and the college’s predominantly Latina/o and black students (see Lehman’s data here), I knew that many, if not all, of my students would be affected by the program, whether the young men targeted or their family members and friends. I also knew they would have experienced racial profiling in its other forms, whether the school-to-prison pipeline in operation at New York City public schools, the general entrapment of the prison-industrial complex and its attendant political economy, or the surveillance of department-store staff and their collusion with police (as experienced by a CUNY student that fall in a high-profile incident).

My pedagogy centers on connecting with students on their terms in order to facilitate critical thinking and discussion about the links between their individual and collective experiences and larger political, social, and economic problematics at local, national, and global scales. This scrutiny extends to the classroom and university, marked by its ongoing exclusion of racialized students (see, for example, here), and disciplinary methods and knowledges (see, for example, Rod Ferguson’s The Reorder of Things), including the very notions of “standard” English and normative academic writing that orient an introductory composition class (see Kevin Brown’s “Rhetoric and the Stoning of Rachel Jeantel,” the first assigned reading).

Indeed, the Zimmerman trial, for instance, in addition to showing the limits of the criminal-justice system for social justice, also highlighted the ongoing subjection of minoritized English speakers, as Martin’s friend Rachel Jeantel was roundly mocked for her testimony. As such, the composition classroom is an ideal space to attend to the verbal dimensions of racial profiling at the same time as its other manifestations.

In this way, the first course readings (see below for full list) addressed the profiling of Jeantel’s rhetoric, affect, and appearance in the context of the authors’ personal experiences vis-a-vis profiling, thus framing the objectives of the course as a whole: a two-fold dynamic in which the students’ own experiences could serve as the initial ground on which to contest hegemonic discourse on race.

This unit, which included Roots’ drummer Questlove’s viral Facebook post about his experiences being profiled, culminated in the first paper assignment, a descriptive/narrative essay in which students intervened in a particular debate over racial profiling using their lived experience as the primary form of evidence. Subsequent units, each tied to a different type of essay writing, focused on multi-modal comparative analysis of popular music and music videos, expository analyses of mass incarceration and the prison-industrial complex, and various arguments opposing stop-and-frisk specifically and racialized security mechanisms generally. The final paper prompt connected the course’s overall discussions to praxis, asking students to make an argument, supported by information from any two course readings, about what aspects of U.S. policing or prisons need to be changed.

Finally, although the oppositional capacity of social media was central to both class discussion and participation (students were required to submit reading responses via Tumblr), I also emphasized social media’s citational limits—that is, the ease with which correct attribution can go awry. This risk was the subject of the first class meeting, in which I handed out copies of a Facebook post quoting “bell hooks on the Zimmerman trial” that went viral —except the quote, from hooks’ 2001 book All About Love, does not specifically address the Zimmerman trial but rather white supremacy at large. Once again, though, it was a prime opportunity to discuss both racial profiling and composition practice.

Detailed Assignment

Per Lehman College English department requirements, English Composition I is not predominantly literature-based, but with this second paper assignment, I introduced literary elements in the form of the lyrics to “Strange Fruit,” originally performed by Billie Holiday in 1939 and later covered by Nina Simone in the mid-1960s, and the lyrics to “Blood on the Leaves,” the 2013 Kanye West track that features Simone singing the lyric “Strange fruit hangin’ from the poplar trees / Blood on the leaves” for its chorus. The paper assignment was to compare and contrast the two songs, which offered the critical challenge of how “Strange Fruit,” based on a poem by Bronx school teacher Abel Meeropol and recorded by Holiday in protest against lynching and revived by Simone at the height of the civil-rights struggle, related to the concerns West raises in his song, namely the complex intersections of romantic relationships and consumeristic bourgeois desires. As such, students had to think about both the literary aspects of each song’s lyrics as well as the differing, but related, historical contexts—that is, the history of U.S. racial oppression in service to white economic power. This history was further emphasized when West performed “Blood on the Leaves” at the MTV Music Video Awards in silhouette against an image of a tree Steve McQueen photographed while making 12 Years a Slave—a performance that generated fresh attention to the song right at the beginning of the semester.

Preparatory class work for writing the paper included lectures by me on the particulars of lynching under Jim Crow, augmented by multi-modal texts available on the course Tumblr and shown in class; close readings of the lyrics and their contexts (aided especially by the annotations of “Blood on the Leaves” on RapGenius.com); and intensive comparative discussion across several class sessions, which yielded an in-class exercise I designed on the basis of the students’ analysis to further hone the possible arguments that could be made (click on the following image for a clear view of the handout).

In the end, although some students remained resistant to seeing any connection between the two songs, everyone was able to see the historical continuum of black pain, on the one hand, and white economic gain, on the other. This lesson effectively set up subsequent class lessons on the continuance of racialized social control in the U.S., including current forms such as stop-and-frisk and mass incarceration. At times it was also entertaining, as all the students had an opinion of West, and they enjoyed discussing pop culture.

Course Readings for Each Unit

Unit 1: the narrative/descriptive essay

- Kevin Browne, “Rhetoric and the Stoning of Rachel Jeantel”

- Mariame Kaba, “Rachel Jeantel: Through a Glass Darkly…”

- Questlove’s Facebook post

- Kim Foster, “Why the Questlove Article Exposes Our Racism—and Our Sexism”

Unit 2: the compare/contrast essay

- Billie Holiday, “Strange Fruit” (lyrics)

- Kanye West, “Blood on the Leaves” (lyrics)

- West, “Blood on the Leaves” (VMA performance)

- Jasiri X, “Blood on the Leaves Remix” (lyrics)

Unit 3: the expository essay

- Angela Davis, “Masked Racism: Reflections on the Prison Industrial Complex”

- Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in The Age of Colorblindness (excerpt)

Unit 4: the argument essay

- Darius Charney, “The NYPD’s Criminal Stop-and-Frisk Record”

- New York Times editorial, “Reform Stop-and-Frisk”

- The Nation video, “Stopped-and-Frisked: ‘For Being a F**cking Mutt'”

- Mimi Kim et al., “A World Without Walls: Stopping Harm and Abolishing the Prison Industrial Complex”

Supplemental readings/texts available on the course Tumblr.